An ambitious plan to end years of repeated flooding on the bayside in Seaside Park has garnered endorsements from officials, residents, environmental advocates and experts in the field of coastal engineering – but it still cannot obtain a federal permit despite far-reaching efforts by the borough.

Both residents and elected officials shared frustrations over the permitting process required to build an artificial reef, new bulkhead and expanded shoreline along Bayview Avenue in Seaside Park. In what has become a routine plague, flooding on the bayside leads to street closures during most full moon high tides or coastal storms, sometimes trapping residents inside (or outside) their homes. Some residents have lost vehicles, others have seen their homes flooded, and still others permanently keep a pair of high boots or waders in the trunk of their vehicles in order to trudge through feet of bay water on their way home from work.

“We’re thrown in the middle of one agency approving our permit, and another saying they wanted modifications that contradicted the other agency,” Mayor John Peterson explained at a meeting of the borough council last week. “Someone indicated that, perhaps, we should just go it alone and do the project.”

That would not be advised, the mayor urged. Indeed, going forward on the project without federal approval would likely be disastrous, the borough attorney advised. Taxpayers would be subject to large fines, attorneys’ fees, with some of the estimates of penalties alone reaching $450,000 to $500,000.

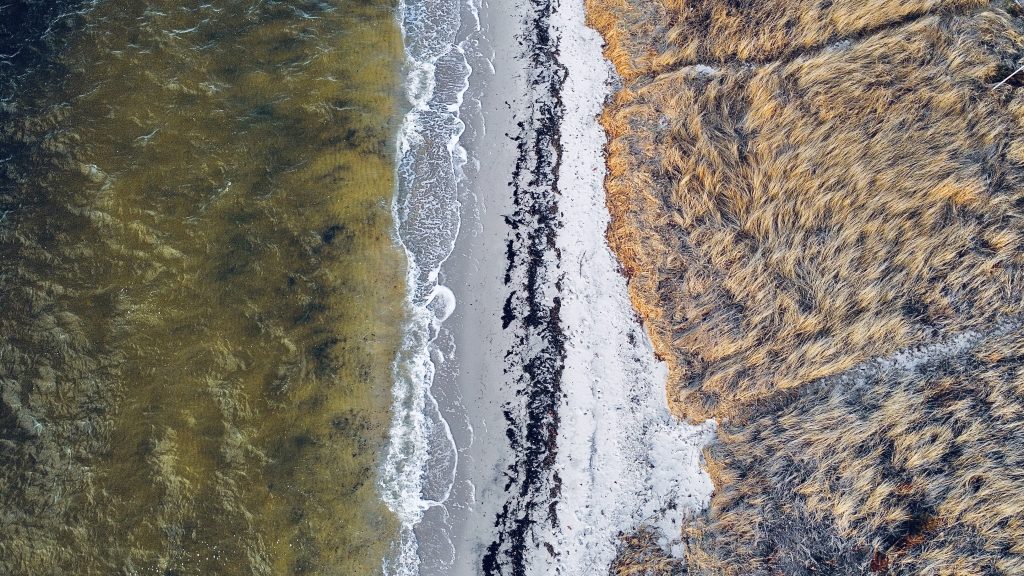

The state Department of Environmental Protection has largely approved of the borough’s plan, which centers on building out a number of platforms on the bayside to mitigate flooding, protect the shoreline, form a breakwater and foster the growth of native species on a “living reef” which would naturally absorb the impact of wave action. In a move few initially thought would be feasible, the borough – with assistance from a team of engineers and academics from Stockton University – were able to convince the state that the shoreline could be safely restored to its former size, as published in a 1977 survey. Expanding the width of the bayfront would not only raise the grade of the shoreline, but leave enough room for a second bulkhead and an oyster reef which would serve the dual purpose of restoring aquatic life to the bayfront and mitigating wave action. The entire effort would be combined with a project to raise the elevation of Bayview Avenue and install check valves on outfall pipes to prevent water from backwashing onto the roadway.

The federal government, on the other hand, has not seen eye-to-eye with the borough – nor the state, for that matter. Seaside Park officials last week said their federal counterparts at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has held up approval of the bayfront protection plan out of a concern over submerged aquatic vegetation, routinely referred to by its acronym “SAV.” In layman’s terms, SAV is what most Jersey Shore residents would refer to as “eel grass” as well as other common aquatic plants that populate the sandy floor of Barnegat Bay. The federal agency argues that the shoreline project would remove “acres” of SAV, but borough officials said there is very little plant life near the water’s edge as it currently stands, and the living shoreline aspect of the project would significantly increase the vegetation present in the area, while also fostering the growth of shellfish and juvenile finfish.

“The issue they’ve raised is SAV, and whether, in terms of mitigation, we have a sufficient plan,” said Peterson, recalling a meeting he attended with Dr. Stuart Farrell, of Stockton, and federal regulators. “We actually walked the water in that meeting – it was a walking meeting, in the water – with Dr. Farrell and others, pointing out to them the very limited amount of plants that would be disturbed by our project.”

In an ironic twist: “The experts suggested that after the oyster reefs took seed and were allowed to grow, it would actually enhance the growth of SAV,” Peterson added.

The borough has gone to extraordinary lengths to appease the federal agency, including offering to pay for a partnership with the Coastal Institute of Virginia – considered a renowned institution for researching SAV – which would have produced a study that could have been used by communities up and down the east coast of the United States facing similar issues.

“They rejected it and said it was not within their regulations,” said Peterson.

Meanwhile, frustration is building among residents who are growing tired of the increasing occurrences of flooding.

“Nuisance flooding occurs at many full moon high tide cycles, but it’s more than a nuisance to the residents by the bay who can’t get out of their houses,” said 10th Avenue resident Mitch Koppelman. “I’m appealing to the council – we need to take action.”

Peterson and members of the council, likewise, expressed frustration and said they would step up engagement with Farrell, other experts in the field, as well as contacts in Washington, D.C. At this point, officials say they simply hope to find someone willing to listen, especially after the state DEP – often referenced as a stringent regulatory agency in its own right – agreed with the borough on the plan’s benefits. The state has also pledged grant funding to help finance the project.

“We said we will guarantee the oyster reefs be allowed to grow, we’ll commit to restocking them if there are any issues, and they rejected that proposal as well,” said Peterson.

For residents, however, the wait is leading to mounting vexation – as well as bills to repair vehicles and homes.

“I’m tired of seeing people having to wade to their houses after work, losing their cars, and emergency vehicles not being able to get through,” Koppelman said.

Advertisement

Seaside Heights & Seaside Park

Seaside Heights Mourns Passing of Boardwalk Legend, Still Working Into His 90s

Seaside Heights & Seaside Park

Construction Projects to Begin in Seaside Park During March

Police, Fire & Courts

Cops: Juvenile Arrested After 118mph Joy Ride in Seaside Heights, Toms River Kills 2

Police, Fire & Courts

Ocean County Sheriff Establishes Drone Command Center in Seaside Heights Amid New Video