A furor among boaters up and down the east coast erupted Thursday as more than 70 representatives of the marine industry, led by the National Marine Manufacturers Association, blasted the federal government for a rule proposal that would limit any vessel between 35 and 65 feet in length to a top speed of 10 knots (11.5 m.p.h.) within about 90 miles of shore for much of the year.

The rule (a copy of which appears online here) is the product of a plan by the Biden administration to reduce the number of vessel strikes on the elusive North Atlantic right whale, an endangered species with only about 350 examples remaining in the wild. But the administration’s own data has shown that there have been just five deadly strikes of right whales by vessels between 35 and 65 feet over the last 15 years – most of which occurred in specific locations known as “calving” areas, rather than the entirety of the east coast from Florida to Massachusetts, as proposed by the government.

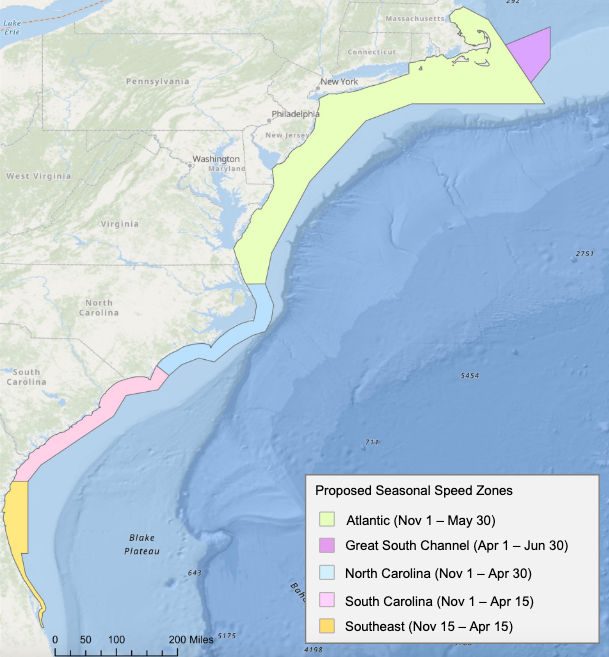

Different coastal states will see slightly different variants of the rule. In New Jersey, boaters would be required to abide by the 10 knot speed limit from Nov. 1 through May 30 each year. The exact coordinates of the speed limit zone, known as a Seasonal Management Area, or SMA, are included in the rulemaking proposal, however the area generally extends about 90 miles from shore.

Presently, there are speed restrictions for boats above 65-feet in length, though only in limited spaces, such as the confluence of Delaware Bay and the Atlantic Ocean and the Great South Channel off Cape Cod. There are no restrictions for smaller boats in any area, at any time of year, besides normal “no wake zone” areas.

The NMMA has warned that the rule could cost $170 billion in lost revenue, affecting more than 70,000 fishing trips each year and more than 63,000 vessels. The issue almost immediately turned political, with conservative commentators accusing the administration of using the issue of right whale protection to limit powerboating and sport-fishing, both of which have been opposed by climate and animal rights activists. The administration, meanwhile, has said the rule is necessary to “reduce vessel strike risk based on a coast-wide collision mortality risk assessment and updated information on right whale distribution, vessel traffic patterns, and vessel strike mortality and serious injury events.”

“Changes to the existing vessel speed regulation are essential to stabilize the ongoing right whale population decline and prevent the species’ extinction,” the rulemaking document states.

The NMMA warned in its letter of sweeping economic consequences if the rule were to come to fruition. The organization estimated 100 million Americans went boating last year.

“The role of recreational boating and fishing in our economy has only grown more significant as Americans flocked to new outdoor activities amidst the COVID-19 pandemic,” the letter stated. “In fact, estimates project the outdoor recreation industry will near $1 trillion in an upcoming economic analysis by the Bureau of Economic Analysis.”

The speed limit will make offshore fishing functionally impossible due to the time it would take to reach fishing grounds, advocates say, and such a slow speed would prevent boats from being able to achieve planing speed – a major safety issue that could cause vessels to take waves over the bow and stress the hull. The NMMA believes the rule will make fishing so unobtainable as a sport – 70 percent of boat trips are for fishing purposes – that the entire industry is likely to be affected.

“Left unchanged, the proposal would curtail thousands of recreational boating and fishing trips each year, jeopardizing billions of dollars of economic impact, thousands of jobs and businesses, and the pastimes of tens of millions of Americans,” the letter said.

A furor among boaters up and down the east coast erupted Thursday as more than 70 representatives of the marine industry, led by the National Marine Manufacturers Association, blasted the federal government for a rule proposal that would limit any vessel between 35 and 65 feet in length to a top speed of 10 knots (11.5 m.p.h.) within about 90 miles of shore for much of the year.

The rule is the product of a plan by the Biden administration to reduce the number of vessel strikes on the elusive North Atlantic right whale, an endangered species with only about 350 examples remaining in the wild. But the administration’s own data has shown that there have been just five deadly strikes of right whales by vessels between 35 and 65 feet over the last 15 years – most of which occurred in specific locations known as “calving” areas, rather than the entirety of the east coast from Florida to Massachusetts, as proposed by the government.

Different coastal states will see slightly different variants of the rule. In New Jersey, boaters would be required to abide by the 10 knot speed limit from Nov. 1 through May 30 each year. The exact coordinates of the speed limit zone, known as a Seasonal Management Area, or SMA, are included in the rulemaking proposal, however the area generally extends about 90 miles from shore.

Presently, there are speed restrictions for boats above 65-feet in length, though only in limited spaces, such as the confluence of Delaware Bay and the Atlantic Ocean and the Great South Channel off Cape Cod. There are no restrictions for smaller boats in any area, at any time of year, besides normal “no wake zone” areas.

The NMMA has warned that the rule could cost $170 billion in lost revenue, affecting more than 70,000 fishing trips each year and more than 63,000 vessels. The issue almost immediately turned political, with conservative commentators accusing the administration of using the issue of right whale protection to limit boating and sport-fishing, both of which have been opposed by climate and animal rights activists. The administration, meanwhile, has said the rule is necessary to “reduce vessel strike risk based on a coast-wide collision mortality risk assessment and updated information on right whale distribution, vessel traffic patterns, and vessel strike mortality and serious injury events.”

“Changes to the existing vessel speed regulation are essential to stabilize the ongoing right whale population decline and prevent the species’ extinction,” the rulemaking document states.

The NMMA warned in its letter of sweeping economic consequences if the rule were to come to fruition. The organization estimated 100 million Americans went boating last year.

“The role of recreational boating and fishing in our economy has only grown more significant as Americans flocked to new outdoor activities amidst the COVID-19 pandemic,” the letter stated. “In fact, estimates project the outdoor recreation industry will near $1 trillion in an upcoming economic analysis by the Bureau of Economic Analysis.”

The speed limit will make offshore fishing functionally impossible due to the time it would take to reach fishing grounds, advocates say, and such a slow speed would prevent boats from being able to achieve planing speed – a major safety issue that could cause vessels to take waves over the bow and stress the hull. The NMMA believes the rule will make fishing so unobtainable as a sport – 70 percent of boat trips are for fishing purposes – that the entire industry is likely to be affected.

“Left unchanged, the proposal would curtail thousands of recreational boating and fishing trips each year, jeopardizing billions of dollars of economic impact, thousands of jobs and businesses, and the pastimes of tens of millions of Americans,” the letter said.

The public comment period on the rule ended Oct. 31, and it remains unknown whether the rule will be finally adopted by the National Marine Fisheries Service in 2023. Regardless, it emerged this week as a new wedge in the national political debate, with interests on both sides sharpening their arguments for a drawn-out legal battle.

Advertisement

Ortley Beach & North Beaches

Landmark Ortley Beach Breakfast Spot Looks to Expand

Ortley Beach & North Beaches

‘Temporary’ 70-Foot Cell Tower on Route 35 in Ocean Beach OK’d to Return

Seaside Heights & Seaside Park

Beloved South Seaside Park Restaurant Will Remain Open As Developer Seeks to Demolish Block

Seaside Heights & Seaside Park

In Seaside Heights, A $50M Flagship Building Rises Over the Boulevard in a Famed Location

Police, Fire & Courts

Ocean County Sheriff Establishes Drone Command Center in Seaside Heights Amid New Video